November 12, 2017 09:40

by Hassen Hussein, Mohammed

Ethiopia is reeling from stubborn anti-government protests and growing fissures within the ruling party. The economy is not doing so well either. High inflation, shortage of foreign currency, and lagging exports prompted authorities to devalue the Birr last month.

But it is the crippling protests and lack of coherence inside the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) that is paralyzing the country.

Protests that began in 2014, concentrated mainly in Oromia, the largest and populous of nine linguistic-based regional states, and to some extent the Amhara State, the country’s second most populous, are still ongoing.

The government decreed a state of emergency in October 2016 to quell the unrest. The decree temporarily stopped street protests but it did little to address the underlying causes. Officials lifted the martial law in August 2017, almost 10 months later, while still leaving the public grievances untouched.

The edict was reimposed on Nov. 10, 2017, by the National Security Council, a body that lacks constitutional muster. As with the emergency law, the latest security measure is spearheaded nominally by the Defense Minister, Siraj Fegessa, a civilian, but in reality by high-ranking military officers.

Fegessa says the militarization was necessary given the deteriorating security situation in the country. But it may have more to do with the deepening cracks within EPRDF, particularly the resurgence of the Oromo associates of the governing coalition, than security concerns.

The Oromo People’s Democratic Organization (OPDO), officially the ruling party in Oromia, is of late acting as though it was an opposition. Asking if OPDO is “the opposition party” in Ethiopia’s confusing state of affairs is a sacrilege. Why? First, OPDO has been a loyal and subservient member of EPRDF for 27 years. The latter is a highly centralized bloc that’s been in power since 1991.Second, EPRDF’s official dogma does not tolerate dissent.

Opposition voices are silenced with the force of the gun or the instruments of law. With the possible exception of Beyene Petros and Lidetu Ayalew every prominent opposition official has faced detention or has been forced to flee the country over the last two decades and a half.

Let alone opposition groups, even civil society organizations and the private media are not immune from EPRDF’s vengeance. It strives to be the sole legal voice in Ethiopia by criminalizing all other voices. The very thought of casting OPDO as an opposition, even rhetorically, therefore speaks to the breadth and depth of changes made possible by three-years of protests by the Oromo, who account for nearly half of the country’s estimated 100 million population.

However, OPDO has unmistakably signaled a shift. Not only did it show new resolve to advance Oromo interests, but it is also increasingly seen as a fresh and refreshing alternative to the status quo by its supporters as well as detractors.

“Why persist with costly street protests when we have made your demands our own? If we failed to deliver using existing legal and institutional mechanisms, I and all of us here will join you in the protests,” Lemma Megersa, OPDO’s newly minted chairman, said in one of his many recent speeches. Lemma receives a hero’s welcome wherever he goes these days—a feat unprecedented in OPDO’s quarter of a century existence.

“Why persist with costly street protests when we have made your demands our own? If we failed to deliver using existing legal and institutional mechanisms, I and all of us here will join you in the protests,” Lemma Megersa, OPDO’s newly minted chairman, said in one of his many recent speeches. Lemma receives a hero’s welcome wherever he goes these days—a feat unprecedented in OPDO’s quarter of a century existence.

This turn of events has confused both those on the ground and many observers watching the situation from afar. Groups who only months earlier were calling for protests to topple the EPRDF regime are seen urging for restraint and calm on cues of the new leaders in Oromia. Among the Oromo, for the most part, OPDO is no longer presented as the previously despised and shunned TPLF puppet but rather fondly as Mootummaa Naannoo Oromiyaa (MNO), the Oromo name for Oromia Regional Government.

The tale of two OPDOs

To understand OPDO’s metamorphosis, one needs to go back to the mid-1980s and the early 1990s.

Since 1974, a military junta known as the Dergue ruled Ethiopia, when it was part of the socialist states allied with the former Soviet Union, with an iron fist. The junta was locked into a life and death tug of war with three liberation groups. The most lethal, the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) fought to break the Eritrean Red Sea coast from Ethiopia and form an independent state of its own. This conflict had been going on for three decades.

Further south, Ethiopian troops battled the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) whose goal was ending the political domination of the Amhara, Ethiopia’s historical rulers, and restoring autonomy for ethnic Tigrayans. The Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), the third rebel group, operated both in the east and west of the country with objectives that alternated between seeking autonomy for the Oromo and forming an independent Oromia Republic. While fiercely independent and jealously guarded their autonomy from it, both TPLF and OLF largely tended to see EPLF as their elder brother and mentor.

Their opposition to the Dergue united the three rebel groups. But they were not on the same wavelength. While comprised predominantly of ethnic Tigrayans, the EPLF and TPLF didn’t always see eye-to-eye on many things other than defeating the massive Dergue army, by then Africa’s largest. Numerous attempts to form alliance between OLF and TPLF, both left-wing movements, failed to materialize. Whereas the latter was fervently communist, in the mold of former Albanian strongman Enver Hoxha, the former was communist in name only and gave primacy to Oromo nationalist ideology.

Toward the end of 1985, TPLF dispatched a company of its elite troops to OLF’s western front ostensibly to exchange best experiences thereby improving relations. However, it instead ended up unraveling the already sore relationship when the unit was discovered trying in vain to covertly recruit OLF members into a rival faction paying allegiance to TPLF’s strictly Marxist and Leninist line.

The relationship between EPLF and OLF remained relatively more cordial. Like OLF, EPLF had also soured on Marxism-Leninism. Besides, the two operated geographically far from each other and didn’t have the love-hate rivalry of cousins that defined TPLF-EPRDF relations. But their relationship wasn’t necessarily free from mistrust emanating from EPLF’s ethnic and cultural affinity with TPLF.

By the end of the 1980s, EPLF and TPLF had shattered the backs of the Dergue army and were contemplating the end game. OLF was just beginning to warm up, growing its support, and applying pressure, after a series of setbacks, both internal and external, that decimated its founding leadership. Contrarily, having overran the Tigray province in a stunning offensive in 1989, TPLF had set its eyes on the ultimate prize: Capturing Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital. To reach Addis, however, it had to cross the vast Amhara and Oromo-inhabited provinces to the south, both hostile territories.

To overcome this hurdle, TPLF first co-opted and brought under its wings the Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement (EPDM), later christened in 1994 as the Amhara National Democratic Movement (ANDM), the current ruling party in the Amhara State. While operating in Amhara-inhabited provinces adjacent to Tigray, EPDM billed itself as a multinational party.

TPLF and EPDM together formed EPRDF in early 1989. With this outfit, TPLF could now cross into the Amhara-speaking provinces on the backs of EPDM.

But what to do about the Oromo?

Having failed to woo the OLF, TPLF scoured the world for Oromo “Democrats,” to use former president of Tigray Region, Gebru Asrat‘s word― willing accomplices who could form a party loyal to TPLF and rival to OLF.1

TPLF spread its nets as widely as Europe and North America looking for Oromo allies. But it could only catch one fish: Dr. Negaso Gidada, one of the many future nominal presidents doting EPRDF’s 27-year-reign. Given his rebellious personality and shifting loyalty, Negaso carried little influence among the Oromo at home and abroad. Curving a space in the Oromo intellectual camp fertile to TPLF’s dream of restoring unrivaled Tigrayan dominance over Ethiopia, a dominion lost with the demise in 1889 of Emperor Yohannes IV, was proving a difficult nut to crack.

TPLF spread its nets as widely as Europe and North America looking for Oromo allies. But it could only catch one fish: Dr. Negaso Gidada, one of the many future nominal presidents doting EPRDF’s 27-year-reign. Given his rebellious personality and shifting loyalty, Negaso carried little influence among the Oromo at home and abroad. Curving a space in the Oromo intellectual camp fertile to TPLF’s dream of restoring unrivaled Tigrayan dominance over Ethiopia, a dominion lost with the demise in 1889 of Emperor Yohannes IV, was proving a difficult nut to crack.

Previously, EPDM had reached out to the princely EPLF, the rebel par excellence, for technical support. The Secretary-General of EPLF at the time, Ramadan Mohammed Nur, proposed two solutions. First, for EPDM to have its own presence, separate from TPLF’s, outside Ethiopia. Second, Ramadan offered to hand over POWs under its captivity. In its 30-year war with Addis Ababa, EPLF had thousands of such captives and it kept them fed, clothed and sheltered in the arid and mountainous environment where it was garrisoned — a Herculean task.

Consequently, EPLF supplied about 300 lower-level Dergue military officers from captivity to EPDM in two consecutive batches. Most were of Oromo descent.

TPLF’s intelligence arm had a daunting problem at hand: How to march into the vast Oromo land without local eyes and ears. That is when Kinfe Gebremedhin, the late head of Ethiopian intelligence, who was killed in 2001 after a bitter fallout within TPLF, stumbled upon a breakthrough: Why not mold the former EPLF captives, then operating with EPDM, into a separate Oromo organization?

That is how OPDO came to be founded in 1990. For the most part, it was made to copy watered down versions of OLF’s political program. To distinguish it from OLF, OPDO was made to advocate for Oromo rights within the context of the Ethiopian state, which was palatable given their previous service to the country, thereby distancing OLF as a separatist movement. And OPDO immediately joined the EPRDF coalition. OLF vigorously protested against what it saw as a betrayal, repeating a familiar pattern of duplicity that so often characterized Oromo-Amhara-Tigrayan group efforts at alliances. It pleaded with EPLF to avert internecine war within the anti-Dergue camp.

During one mediation effort, held in Sen’afe, Eritrea, Meles Zenawi, Ethiopia’s future Prime Minister, offered to disband OPDO and hand them over to its nemesis, the OLF. Caught off guard by the unexpected concession, the OLF delegation led by Lencho Leta, already used to Zenawi’s theatrical performances, first gave out a poker face. Come the morning, Zenawi’s colleagues, including Siye Abraha, Ethiopia’s future defense minister, had talked him out of the “crazy” idea.

Meles Zenawi’s OPDO

During the transition period, TPLF watched, not impartially, as OLF and OPDO battled for the hearts and minds of the Oromo.2 It soon dawned on it that OPDO had no chance against OLF in this effort. Consequently, TPLF brought in its military muscle on the side of OPDO, forcing OLF to leave the transitional arrangement in July 1992 and subsequently resume armed struggle.

EPRDF was able to subdue the OLF militarily, but it could not cleanse OLF’s credo from Oromo hearts and minds. OPDO vacillated between mimicking and copying OLF and violently suppressing such dalliance at other times. It also served as a bogeyman and scarecrow to frighten the Amhara opposition, which saw the curving up of Ethiopia into a multinational federation as a mortal threat to “national unity.”

For all intents and purposes, by late 1990s, OLF’s low-level insurgency had come to an end. After overcoming the shock of being outgunned and outmaneuvered in 1992, OLF showed a remarkable revival, especially in Eastern and Southeastern Oromia, between 1994 and 1996. However, it couldn’t sustain this rally and its operational capacity began to decline in early 1997 and sputtered in 1999 (the 1998-2000 Ethio-Eritrean war lent some life to it but this too was short-lived).

In the new millennia, if OPDO’s birth was a reaction to OLF’s existence and prowess, the latter’s decline corresponded with growing confusion and discontents within OPDO’s ranks.

When OLF was active, TPLF needed, hence respected, the OPDO. Now that OLF was no longer a threat, TPLF honchos paid no heed to its subservient partner.

Tensions briefly came to a boil in 2001, in the aftermath of a crushing split among TPLF’s leadership. Some in the OPDO used the opening provided by TPLF’s internal rupture to press for more autonomy. While Kuma Demeksa, then-president of Oromia, and Negaso, Ethiopia’s nominal president at the time, sided with the dissident TPLF faction and were sidelined, the remaining OPDO leadership sat in a month-long meeting headed by Meles Zenawi, then Chairman of TPLF and Prime Minister.

Zenawi made lots of promises. One such promise was to end TPLF stewardship of OPDO. Accordingly, Bitew Belay, who until then minded Oromia and the southern region as TPLF’s viceroy, was removed—even though the tutelage continued in other less overt ways. Another promise was to invite Oromo intellectuals into OPDO’s fold. He made good on this promise by recruiting Juneydi Sado, who was until then unaffiliated to OPDO, as the president of Oromia State, at the OPDO Congress held in Naqamte in 2002.

Zenawi made lots of promises. One such promise was to end TPLF stewardship of OPDO. Accordingly, Bitew Belay, who until then minded Oromia and the southern region as TPLF’s viceroy, was removed—even though the tutelage continued in other less overt ways. Another promise was to invite Oromo intellectuals into OPDO’s fold. He made good on this promise by recruiting Juneydi Sado, who was until then unaffiliated to OPDO, as the president of Oromia State, at the OPDO Congress held in Naqamte in 2002.

To ensure that Juneydi didn’t overplay his hands, Zenawi brought in Abba Dula Gamada, then a Major General and Minister of Defense, as party Chairman. Abba Dula had played a starring role in defeating TPLF dissidents who had threatened Zenawi’s hold on power. While Juneydi focused his efforts on institutionalizing and professionalizing the Oromia bureaucracy and public services, Abba Dula went into an aggressive recruitment drive quadrupling OPDO’s membership. After being routed by the opposition in the 2005 elections, Zenawi was done taking risks and decided to concentrate leadership of OPDO and the Oromia regional government in Abba Dula’s loyal hands.

Abba Dula took over at the helm in 2006 with the full trust and backing of Zenawi. At the same time, the new president of Oromia and OPDO chief was by far the most hated by Oromo activists. In fact, many refused to call him Abba Dula, instead referring to him as Minase Woldegiorgis. But he went onto reshape the OPDO, the Oromia state, and the Oromo people’s struggle for years, and perhaps even for decades, to come. First, he used his platform to organize and galvanize a fledgling Oromo business class, catapulting them into playing a more active role in the region’s economy.

Second, he continued with his membership drive. OPDO’s much-touted 4,000,000 membership owes to this drive. Most of those recruited into the OPDO were new college graduates, including those who had been active in the protest movement centered around university and college campuses.

Third, he launched large infrastructural projects, including the establishment of new universities — a work started by his predecessor, Juneydi. Fourth, he reached out to the Oromo public in a way that had heretofore not seen. In his short tenure of four years, Abba Dula became a household name in Oromia. Fifth, through this outreach, he dried the well that previously allowed OLF to survive at least as a ghost overshadowing his OPDO. His tentacles even reached all the way to the Oromo diaspora where opposition to OPDO had been almost universal.

Abba Dula’s popularity earned him a grudging respect among many in the Oromo nationalist camp, but it also raised fears with Zenawi. Accordingly, against the unanimous opposition of OPDO’s rank and file and his own expressed wishes, in the 2010 elections, Zenawi forced Abba Dula to run for the federal, rather than the regional parliament. To accomplish this, Zenawi reached out to his loyal OPDO faction led by Kuma, who by then had regained Zenawi’s trust. The faction included in its ranks Aster Mamo and Muktar Kadir. Aster was brought into the limelight through Azeb Mesfin, the Prime Minister’s wife. Muktar rose through OPDO’s ranks and was at the time serving as the Prime Minister’s office as Zenawi’s protégé.

Abba Dula’s popularity earned him a grudging respect among many in the Oromo nationalist camp, but it also raised fears with Zenawi. Accordingly, against the unanimous opposition of OPDO’s rank and file and his own expressed wishes, in the 2010 elections, Zenawi forced Abba Dula to run for the federal, rather than the regional parliament. To accomplish this, Zenawi reached out to his loyal OPDO faction led by Kuma, who by then had regained Zenawi’s trust. The faction included in its ranks Aster Mamo and Muktar Kadir. Aster was brought into the limelight through Azeb Mesfin, the Prime Minister’s wife. Muktar rose through OPDO’s ranks and was at the time serving as the Prime Minister’s office as Zenawi’s protégé.

There were two major speculations in the months before the 2010 elections. One said it’s time for an Oromo prime minister, which was and has been a ruse to mollify OPDO and defuse pressure from the Oromo public. The second rumor posited that Abba Dula was immersed in corruption up to his neck and that he would go to jail. Zenawi’s loyalists furtively collected and piled all the dirt they could find on Abba Dula.

In the organizational conference following the election, Abba Dula’s supporters were in disarray but they somehow managed to force a compromise that resulted in Alemayehu Atomsa’s elevation as president of Oromia and chief of OPDO (Abba Dula’s compromise with Kuma’s faction reportedly angered the nationalist wing of the party which four years later would take over the organization).

Having broken Abba Dula’s grip on Oromia and OPDO, Zenawi figured that Abba Dula was more useful as the Speaker of the House rather than a prisoner. Besides, parliament was a nominal body and hence a boring assignment for Abba Dula. While reluctantly making himself at home in his pseudo speakership position, thanks to his charms and warmth Abba Dula ingratiated himself to the MPs while keeping his hands close to the pulse on Oromia. With the untimely death of Alemayehu from an unknown illness, Muktar and Aster took the helm in Oromia in March 2012. This carefully choreographed master and willing servant arrangement between TPLF and OPDO began to come unglued with the death of Zenawi in August 2012.

OPDO post-Meles

For most of its 27-year history, OPDO personified the humiliation of the Oromo people. The embattled party held a pitifully marginal status in the EPRDF behind TPLF and ANDM and it allowed the dominant TPLF to ride roughshod over the Oromo populace.

On the one hand, OPDO is presented as the representative of the Oromo in EPRDF; on the other hand, as executors of TPLF’s hardline policy on the Oromo. As a result of the dissonance caused by the conflicting expectation placed on it, a large number of the party’s founding members and leaders left the organization and the country in disgust.3 An ever larger number faced purges for refusing to accept the OPDO’s status as the perennial TPLF Trojan Horse. The party’s primary grievance was the federation was by name only and that the constitutional promises of regional autonomy were flagrantly violated by TPLF.

This begun to change in May 2014 when enraged members of the OPDO spoke out forcefully against the so-called Addis Ababa master plan, which would have significantly expanded the Ethiopian capital’s territorial jurisdiction into Oromia.

#OromoProtests and the rebirth of OPDO

The Master Plan, which sought to make a huge wealth transfer from poor Oromo farmers to the new oligarchy, was the straw that broke the camel’s back. It brought into clear focus and encapsulated all past grievances and frustrations. The plan was first introduced to OPDO cadres in Adama, where it unusually set off an uproar. In a departure from the previous practice of kowtowing the official line, opposition to the Master Plan was covered by the regional TV Oromiya, setting off statewide protests that would continue until October 2016 when Ethiopia declared a state of emergency. 4

“The issue of Addis Ababa and surrounding Oromia region is not a question of towns; it is a question of identity,” said Takele Uma, now the head of Oromia’s transport authority, at a workshop in Adama.

“When we speak of identity, there are fundamental steps we ought to take to ensure that the plan would incorporate and develop the surrounding towns while also protecting Oromo’s economic, political, and historical rights.”

Takele added: “We are keenly aware of the city’s past spatial growth. We don’t want a city that pushes out farmers and their children but one that accepts and develops with them…more importantly, we don’t want a master plan developed by one party and pushed down our throats.”

His comments reverberated across Oromia. “No to Addis Ababa master plan,” chanted the youth in their hundreds of thousands—town after town. The federal security forces responded with a brutal crackdown, arresting tens of thousands and killing more than 1000 people in 2016 alone. But nothing would quell the protests. The Oromo has risen and finally said enough. Protests even spread to the Amhara region and parts of southern nations, nationalities, and people’s region.

In October, after imposing martial law, EPRDF ostensibly launched a “deep reform” campaign with the aim of addressing the mounting public grievances. But it quickly sidestepped those demands using such euphemisms as governance bottlenecks and corruption. However, dissent voices within OPDO, who were incensed by the violent repression of peaceful protesters, used the occasion to respond positively to popular demands. Rather than skirting around popular demands that the regime reluctantly acknowledged as legitimate, the party adopted them by electing their own leaders without central imposition — for the very first time.

Previously OPDO leaders were handpicked by TPLF and communicated through the EPRDF head-office. TPLF held significant sway over the EPRDF executive committee that “recommended” regional party leaders.

But, this time, the nationalist-wing prevailed and ended its humiliating debacle by forcing the resignation of the party’s chairman and deputy chair. After 27 years of subservience, OPDO began to show signs of assertiveness. It quickly launched a swift campaign to earn the public’s trust: First by demanding that foreign cement producers share control of mines with the region’s unemployed youth.

View image on Twitter

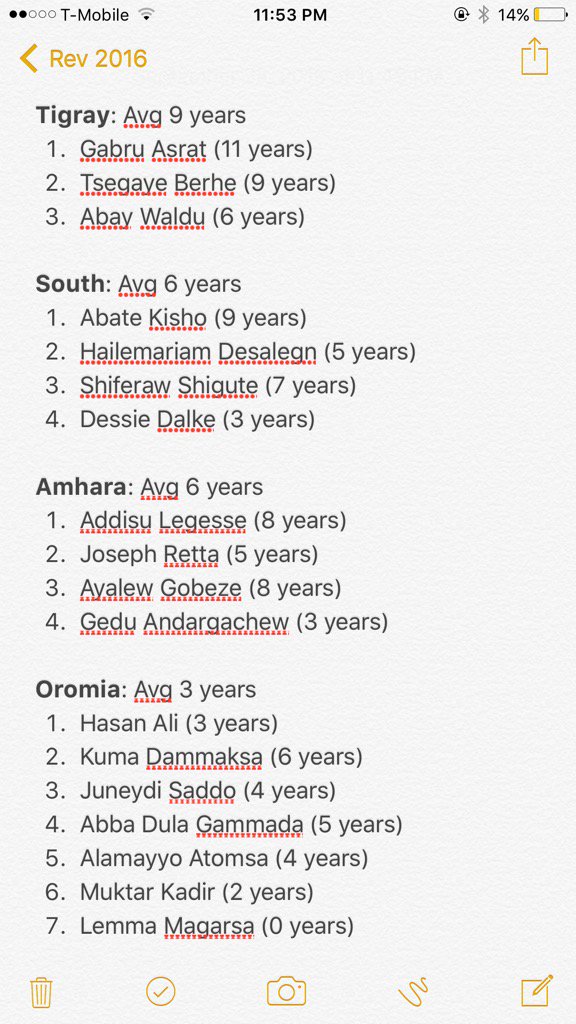

Hassen Hussein @AbbaKayo

Why urgency on OPDO’s Lemma? Oromia presidents have shortest tenure. If demands of #OromoProtests unmet? Woe woe!

8:58 PM – Sep 23, 2016

33 Replies

99 Retweets

44 likes

Twitter Ads info and privacy

The new leaders also began a massive audit of land deals across Oromia, particularly in towns near Addis Ababa, and repossessed undeveloped or underdeveloped plots held by shadowy investors. Meanwhile, the regional broadcaster launched its own rebranding campaign—both physically and editorially.

It went from TV Oromiya to Oromia Broadcasting Network (OBN) with a motto of “voice of the people.” Editorially, in a sharp departure from a hitherto obsession with “developmental journalism,” OBN began to churn out investigative reports, including reports on illegal land deals. It also broadcast speeches and town hall meetings attended by the new leadership where constituents openly vented their pent-up anger and frustration.

It went from TV Oromiya to Oromia Broadcasting Network (OBN) with a motto of “voice of the people.” Editorially, in a sharp departure from a hitherto obsession with “developmental journalism,” OBN began to churn out investigative reports, including reports on illegal land deals. It also broadcast speeches and town hall meetings attended by the new leadership where constituents openly vented their pent-up anger and frustration.

AFTER the 2014 protests, Speaker Abba Dula reportedly warned the federal government, including the prime minister, that, despite a lull in protests, all was not well in the restive state. Privately, he reportedly confided to associates that despite criticism of OPDO’s lackluster performance, under its watch, Oromia has produced one of the bravest generations ever to grace the land who could never be intimidated. When the feared Oromo youth explosion returned in November 2015, Abba Dula felt as vindicated as powerless. The protests managed to sustain itself and eventually led to the downfall of Muktar and Aster and rise of a dynamic duo—Lemma and Abiy Ahmed.

A year after the OPDO renewal commenced, on October 8, 2017, Abba Dula resigned from his post as Speaker of the House of People’s Representatives, protesting what he termed “disrespect to his party and people.”

Two weeks later, on October 29, 2017, 177 members of parliament, a third of the body, mostly from Oromia, boycotted a joint session where the sitting prime minister defended his government’s new year agenda. The PM also faced unusually sharp and critical questions from previously docile MPs. Even more ominously, a great mass of invitees skipped the annual state dinner reception held for MPs of both Houses of Parliament. Present were a mere 7 Oromo, only a third of the Amhara delegates, and a small number from the Benishangul Gumuz and Gambela regions.

2017 OPDO Congress

On October 29, 2017, OPDO reached another milestone: For the first time in its history, the party adopted its own meeting agenda, which reflected the grievances and aspirations of the people they were supposed to represent, the key plank of which is a judicious implementation of the country’s federal constitution. Previously, OPDO simply rubber-stamped the agenda, resolutions, and other diktats sent from the central party office.

To be clear, OPDO leaders did not wake up one morning, snap their fingers and decide to change the humiliating course they have been on for more than quarter a century. The party’s remarkable turnaround is as gradual as methodical, not to mention the accident of history. Why so? Because it could not even be conceived, let alone be realized, had it not been for the struggles waged by Oromo nationalists for decades and the unrelenting youth-led protests that engulfed Ethiopia since April 2014. Practically speaking, the new OPDO leadership is a child of the Oromo protests—not to mention the vacuum left by Zenawi’s death.

Wherever the OPDO went to calm down the public, it ran into a wall. The question from all sectors of society was always one and the same: If this was a federation, why are the Oromo not proportionally represented in the federal army which terrorizes children and women and kill our youth? No explanation was enough. “Don’t tell us anything else; can you get the bloodthirsty federal police and army units out of our villages?”

Unable to contain a popular grassroots movement to end the oppression and marginalization of the Oromo, OPDO has to adjust, bucking the resistance from central leaders. As a result, OPDO, a party in ascendancy, is now pitted against TPLF, the previous hegemon and a party in the throes of an excruciating decline.

OPDO’s uncertain future

There are and have always been factions within the OPDO. However, there is also a total agreement among the new leadership and the majority of party’s rank-and-file that their subservient role within EPRDF and the marginalization of the Oromo from federal structures are totally unacceptable. Toward that end, they are pushing for real change and reforms. It isn’t like they have a choice: The Oromo public, who has proven an autonomous force to reckon with, is breathing down their neck.

The public has forced OPDO to sideline those still loyal to TPLF and EPRDF’s authoritarian legacy. And the OPDO knows full well that they couldn’t take the public’s support for granted. The Oromo simply gave its benefit of a doubt, which it can withdraw if OPDO failed to deliver. Having seen how defiant the youth protesters, the Qeerroo, blunted the edge of the emergency rule, OPDO doesn’t have any reasons to doubt that the public will back down from asking and getting what it wants from the regional and federal state.

Lemma once remarked that Ethiopia’s rulers have not fully grasped how far the Oromo popular mobilization has advanced and warned against underestimating its resolve to meet all challenges, be it internal or external.

To say the least, OPDO’s rise under its mercurial and charismatic leader has stoked fears within the TPLF oligarchy that is used to running the country and regions as their little fiefdoms. TPLF-affiliated media has been in overdrive to discredit the new direction taken by OPDO.

So far, TPLF had tried three approaches to bring the new OPDO leadership under its orbit. First, it unleashed a proxy war using the Somali region’s paramilitary force, the Liyu Police, to invade Oromia districts and villages along the common border, killing hundreds and displacing close to half a million. Rather than cow the OPDO and the Oromo into submission, the blatant aggression stoked a unity and solidified support for the new OPDO leadership among the disgruntled Oromo public, especially the youth.

Second, TPLF, in a bid to make Oromia unstable and ungovernable, deployed its clandestine agents to exploit differences within the OPDO itself and to mobilize opportunists and rogue elements at the zonal and district levels too eager to do TPLF’s bidding. However, this also didn’t take TPLF’s agenda in Oromia far enough. Instead, it resulted in the unintended consequence of helping the new OPDO leadership further consolidate power by purging and distancing TPLF lackeys.

Third, TPLF used its vast intelligence networks throughout the country to saw hostility between the Oromo and other Ethiopian nationals residing in Oromia for generations, mainly the Amhara. This too produced an effect unintended by TPLF: It brought the Oromia and Amhara state officials closer in a way not seen before.

Fourth, using the instability concocted and fostered by its agent provocateurs, TPLF sought to once again bring Oromia under martial law. This too came to naught thanks to a budding rapprochement between ANDM and OPDO, who together hold more than 67 percent of the seats in the federal parliament, the body that has, at least on paper, the ultimate powers to declare an emergency rule.

ANDM-OPDO bromance: the best hope for Ethiopia?

Lemma and the new leaders in Oromia continue to hit the right notes, openly scolding rent-seekers, entrenched robber barons and their media associates for wanting to destabilize the state and the country. They continue to champion the grievances and aspirations of the Oromo as well as the Ethiopian people for implementing the spirit and letter of the federal constitution. With their overtures to the Amhara, via two recent initiatives, the Xaanaan Keenyaa (Tana is ours) dabo, in which Oromia sent its youth to help to fight invasive water hyacinth on Lake Tana, and the recent Bahir Dar forum, OPDO is indeed charting a new path for the future of the country and its diverse population.

![]() Kassahun Andualem @AndualemKasahun

Kassahun Andualem @AndualemKasahun

Both Amhara and Oromo youths @ Lake TANA – Bahir Dar Ethiopia.

4:55 AM – Oct 13, 2017

Replies

Retweets

likes

Twitter Ads info and privacy

With these bold moves, OPDO has literally eviscerated a few of the thorniest issues standing in the way of inter-communal harmony between Ethiopia’s two largest nations, the Amhara and the Oromo. This move has obviously unnerved TPLF hardliners. Their media outlets have been courting ANDM in a bizarre and brazen manner. At the same time, ANDM’s leadership is yet to undergo the kind of remake OPDO experienced with its “deep renewal” and it is not certain the bromance will hold for long. To make matters worse, some of the agenda being pushed by OPDO, such as Oromia’s Special Interest on Addis Ababa, are those that have historically been unpalatable to the ”pro-unity“ camp if not necessarily to ANDM’s sympathizers in the capital.

TPLF: A cornered tiger?

There is an Oromo saying that Lemma uses frequently: You won’t take hold of a tiger’s tail but once you do, you never let it go. TPLF is clearly a cornered tiger, its sharp teeth are intact, and it is still plotting its options. Its central committee has been meeting in Mekelle since early October to formulate policies and strategies that can safeguard its interests in Addis Ababa and its hold on the country.

Many fear that TPLF would resolve to use its dominance in the top brass of the military and intelligence services to quash the threat posed by the new OPDO and Oromo protests. Should this come to pass, the fear is that Oromia will be drenched in blood. The current generation of youth, who make up over 70 percent of the state’s population, is unlikely to allow TPLF to play roughshod over MNO, as well as the Oromo public. Even if OPDO fails to deliver or prevented to do so by TPLF, the youth doesn’t seem to stop at nothing, including storming the national palace.

Although skeptics abound, the OPDO has galvanized the Oromo in ways not witnessed before and it is winning the public’s one-time reluctant support. In fact, there is growing pressure on OPDO from within and without to assume leadership of the ruling party and the country. However, it still has a long way to go to have the organizational capacity to fully realize the aspiration of the Oromo people: Meaningful self-rule and equitable representation in the country’s federal institutions. Many still question the party’s seriousness and readiness, not to mention its real motive.

This skepticism is reinforced by the fact that TPLF still controls all of the country’s instruments of coercion. The generals are too involved in business (many reportedly own premium real estate in Addis Ababa) and illicit or contraband trade. Their elaborate patronage system could unravel with the collapse of Tigrayan hegemony. Hence, they have a huge stake in keeping the status quo in place if they are unable to reverse things back to where they were before the protests. But will the rank and file, the average soldier, loyally execute another unpopular state of emergency?

A new martial law by another name

Having failed to decree a new martial rule through parliament as well as the EPRDF Executive Committee, TPLF and its allies are apparently resorting to the heretofore unused National Security Council, an advisory body with fleeting legal ground, to reinstate the same Command Post structures put in place in preparation for the October 2016 emergency decree. This too may end up being another futile attempt at plugging the floodgates.

Even without the army, TPLF still has the will and ability to subvert the OPDO from multiple directions. There is no illusion that it will play nice and allow OPDO’s new vision to prevail at the March 2018 EPRDF Congress, the highest decision-making body that meets every two to two-and-half years.

The conventional wisdom is that TPLF would either take cosmetic overtures to OPDO, such as breaking the Gordian knot with Somali regional president Abdi Iley and his Liyu Police, who proved to be the albatross on TPLF’s neck. Or it would escalate the confrontation with OPDO and end up taking the country to the brink of civil war. Giving in without a fight to the core demands of a force for which it has so much contempt is unthinkable.

In this regard, OPDO hasn’t answered some unavoidable questions: What will it do when the federal special forces, the Agazi, mounted atop tanks, come marching with machine guns as they did to kick out OLF (1992), crush the Coalition for Unity and Democracy (2006) and silence Dimsachin Yisema (2014)? What will it do when TPLF weaponizes the courts to come after key OPDO leaders? These questions are bound to come and OPDO has not yet answered them. And the answer isn’t saying our people will match up better against tanks.

Nevertheless, TPLF’s stranglehold on Ethiopia is clearly waning. TPLF no longer holds the superiority in governing ideas that it had for nearly two decades and a half under Meles. OPDO’s new leadership outclasses TPLF’s not only intellectually but also in their ability to inspire, mobilize and organize. Yet, given its utter contempt for OPDO, TPLF may find it difficult to accept OPDO as an equal partner, let alone the new big kid on the block—hence why its emotion may trump its reason.

The historian Thucydides tells us that war becomes inevitable when a unique historical circumstance comes to pass: When an emerging force threatens the supremacy of an established hegemon that is on a decline. Under Ethiopia’s current circumstances, the Oromo in general and the OPDO, in particular, are rising. And TPLF, the established and dominant force, unmistakably on a downward slump.

The historian Thucydides tells us that war becomes inevitable when a unique historical circumstance comes to pass: When an emerging force threatens the supremacy of an established hegemon that is on a decline. Under Ethiopia’s current circumstances, the Oromo in general and the OPDO, in particular, are rising. And TPLF, the established and dominant force, unmistakably on a downward slump.

To reiterate, they both have their vulnerabilities. OPDO has yet to prove its mettle with the Oromo public by enacting desired policy reforms and changing their daily lives in a meaningful way. Knowing the impatience within the Oromo camp, TPLF can simply delay and stall and wait for a more opportune time to strike. It could physically liquidate some of the key MNO leaders.

TPLF’s main bottleneck is that its own house isn’t in order. Since Zenawi’s untimely death, TPLF has failed to produce a leader of his stature and influence that transcends the Tigrayan region. At the same time, TPLF can still count on Abdi Illey and his Liyu Police in the Somali region as well as sympathizers in the Southern region.

The loyalty of the current Prime Minister, Hailemariam Desalegn, who lacks his own anchoring vision as a leader and a distinct power base is uncertain. Of the southern movement he leads, the Sidama, the largest of many smaller groupings, want genuine representation that is commensurate with their size. It is worth noting here that TPLF hardliners have lately faulted Hailemariam for endorsing OPDO’s versions of events, especially on the bloody rancor between Oromia and the Somali regional state.

Regardless, TPLF still has one additional advantage that allowed it to weather many previous storms: Cordial relations with the international community as well as regional (African) governments. Its success in isolating Eritrea is coming to an end, but TPLF leaders still have their international backers.

The Ethiopian military is viewed as the bulwark for regional stability, including by the United States. Its role in preventing Al-Shabab’s takeover of Somalia and the total collapse of South Sudan is a major source of international and regional legitimacy. To play into Western fears of the rise of radical Islam, TPLF would leave no stone unturned, including fanning religious radicalization, religiously motivated conflicts, and inter-communal tensions.

Still, the up and coming Oromo ascendancy have passed the stage where it can be easily thwarted either by TPLF’s monopoly over the military and security services or its uncanny ability to subvert, perfected over the last 40 years. With his victory lap to the northern lakeside city of Bahir Dar, Lemma is already looking like Ethiopia’s new leader. He has the charisma. He has the eloquence. He has the base. He knows the ins and outs of the current system. He has his hand on the pulse of the country’s youthful and dynamic population, the Oromo.

Still, the up and coming Oromo ascendancy have passed the stage where it can be easily thwarted either by TPLF’s monopoly over the military and security services or its uncanny ability to subvert, perfected over the last 40 years. With his victory lap to the northern lakeside city of Bahir Dar, Lemma is already looking like Ethiopia’s new leader. He has the charisma. He has the eloquence. He has the base. He knows the ins and outs of the current system. He has his hand on the pulse of the country’s youthful and dynamic population, the Oromo.

Prime Minister Lemma?

Ethiopian history tells us three things about transfer of power. One, transitions are rarely products of compromises between rival factions but the victory of one group over another. With the departure of Abba Dula — the last bridge between TPLF and OPDO — a negotiated outcome is hard to fathom at this point. We are already seeing the power play and the jockeying.

Two, that the country experiences sustained chaos following a leader’s death or downfall. After Zenawi’s demise in 2012, Ethiopia has indeed been in turmoil.

Third, the chaos ends with the rise of a victor, a new strong leader. Would Lemma be the strong leader that finally ends Ethiopia’s harrowing instability? Given his base and wits, Lemma is unlikely to follow the footsteps of Hailemariam, the embattled current prime minister, who is seen as a puppet of Tigrayan ministers, special advisors, generals, and intelligence bosses.

Shedding its evolving status as a governing opposition party, will the OPDO become a real political organization that can resolve Ethiopia’s historical ills, including its original sin of marginalizing its majority Oromo population?

Time will tell.

Asrat, G. (2014). Sovereignty and democracy (in Amharic),,Signature Book Printing Press. Gebru Asrat, a long time TPLF leader, was the chief administrator of the Tigrean National State from 1994-2001.

Meles Zenawi used to remark that OPDO was like a scratch off lottery ticket: You scratch an OPDO and you are sure to find a disguised OLF.

The most notable defections include the first Oromia regional president Hassan Ali (1998), Speaker of the House of federation Almaz Mako (2000), generals Kamal Galchu and Hailu Gonfa (2006), Juneydi Sado, Oromia’s third president (2012), and a dozen bureau heads.

At least 18 Oromo journalists, including the anchor of that news segment, were subsequently fired from Oromia Radio and Television Organization